This article was originally published in Verdict magazine (Vol. 31, No. 4, October 2025), a publication of the National Coalition of Concerned Legal Professionals.

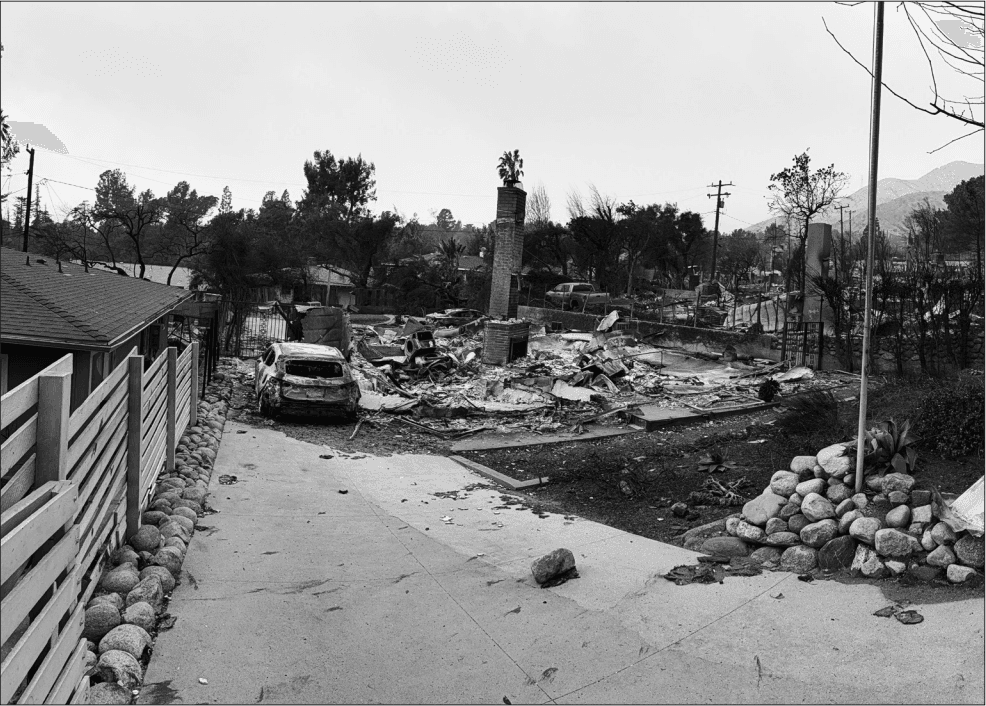

Editor’s Note: On the morning of January 7, 2025, one of the deadliest series of wildfires in Los Angeles County history began with flames roaring down the Santa Monica Mountains and setting the Palisades neighborhood of an unprepared city ablaze. Within hours, a second fire began to engulf the Los Angeles suburb of Altadena. The flames spread rapidly due to drought conditions and Santa Ana winds up to 90 miles per hour, the strength of a Category 1 hurricane.

Before the fires were contained more than three weeks later, California officials would list the death toll at 31. The result of a more recent study by Boston University’s School of Public Health and the University of Helsinki, appearing in the August 6, 2025 Journal of American Medicine, estimates the real death toll at 440. The accounts of events surrounding the fires depicted chaos, with many residents left to their own devices to attempt to protect their properties and/or evacuate, without government assistance, in the face of an oncoming wall of flames. While at one point almost 200,000 Los Angeles residents were under evacuation orders, the Los Angeles Times reported that many Altadena residents received evacuation orders late, in some cases when flames where already on their block, or not at all.

In addition, firefighters battling the flames reported low water pressure or hydrants completely dry. The three Los Angeles Department of Water and Power water tanks of one million gallons each were empty less than 24 hours after the fires started. The 117-million gallon Santa Ynez Reservoir in the center of the Palisades neighborhood was closed for repairs. Moreover, Los Angeles County Public Works Director Mark Pestrella said the city’s municipal water system is “not designed to fight wildfires.”

The catastrophic human toll is compounded by the staggering economic toll. The L.A. fires destroyed more than 16,000 buildings and 40,000 acres of land. The UCLA School of Management estimates that “total property and capital losses could range between $76 billion and $131 billion, with insured losses estimated up to $45 billion,“ a “0.48% decline in county-level GDP for 2025, amounting to approximately $4.6 billion” and a “total wage loss of $297 million for local businesses and employees in the affected areas.”

Even before the fires started, thousands of L.A. residents lost insurance, as insurers withdrew their coverage or refused new policies, citing skyrocketing risk due to increasing numbers of climate-change driven events. As the authors discuss, many residents were forced into the state-run FAIR Plan, with its higher premiums and myriad problems, or became uninsured. Many attempting to rebuild face almost insurmoutable bureaucractic hurdles. If they are insured, many face an unaffordable gap between rebuilding costs and insurance payouts. Many will never rebuild. Others await the results of L.A. County’s lawsuit against Southern California Edison, alleging that Edison’s failure to maintain its equipment caused sparks to ignite the surrounding dry vegetation, causing the Eaton Fire that leveled Altadena, and that Edison had notice of impending high winds days before the fire started.

Moreover, the National Center for Environmental Information reports that in 2024 there were 27 confirmed weather/climate disaster events in the U.S. with losses exceeding $1 billion, a trend that is expected to continue.

I. Introduction: Scorched Earth, Shaky Promises

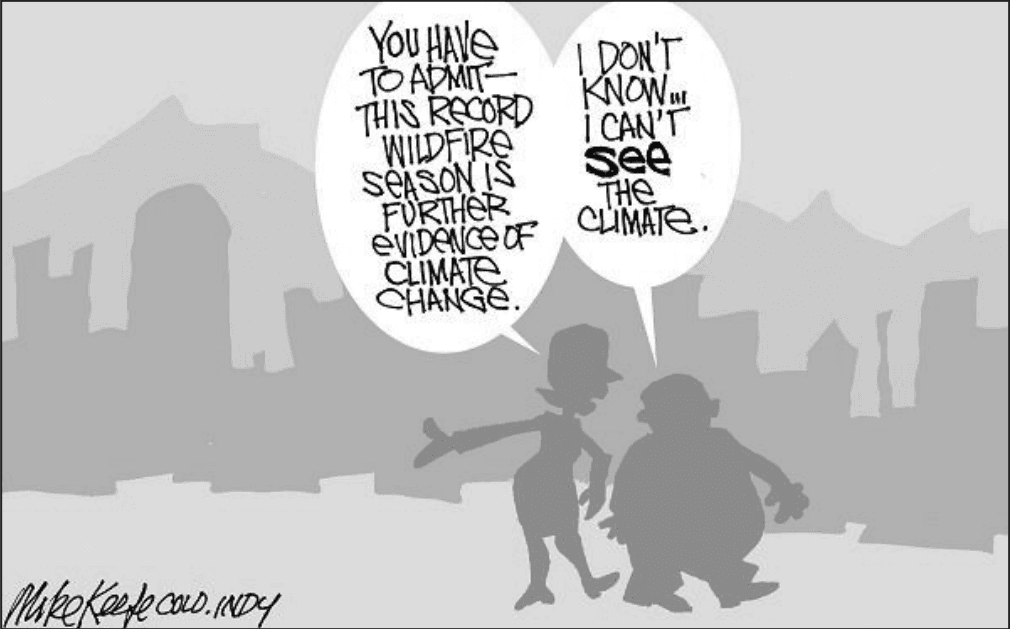

California’s wildfire season no longer feels seasonal — it is relentless, devastating, and increasingly predictable. The causes range from prolonged drought and record heatwaves to utility infrastructure failures and mismanagement of forest land. These fires leave behind physical ruins and emotional devastation, but for many Californians, the second catastrophe strikes when they turn to their insurers. What should be a source of security becomes a bureaucratic gauntlet of delays, denials, and underpayments.

More troubling are the growing allegations that these insurance challenges may not stem from individual corporate decisions alone, but from coordinated industry-wide behavior. Reports are surfacing that suggest insurers are acting in concert — whether explicitly or tacitly — to reduce exposure to fire-prone regions. Policy cancellations, non-renewals, and the use of opaque risk-scoring algorithms appear to be more synchronized than random. If such practices amount to collusion, they may violate multiple provisions under California and federal law.

This article examines the legal implications of potential insurance collusion in California’s post-wildfire landscape. It reviews the current wildfire-insurance dynamic, unpacks the nature of alleged collusive conduct, and considers how existing laws might apply to what could become one of the most significant consumer protection battles of the climate era.

II. Background: A Climate of Fire and

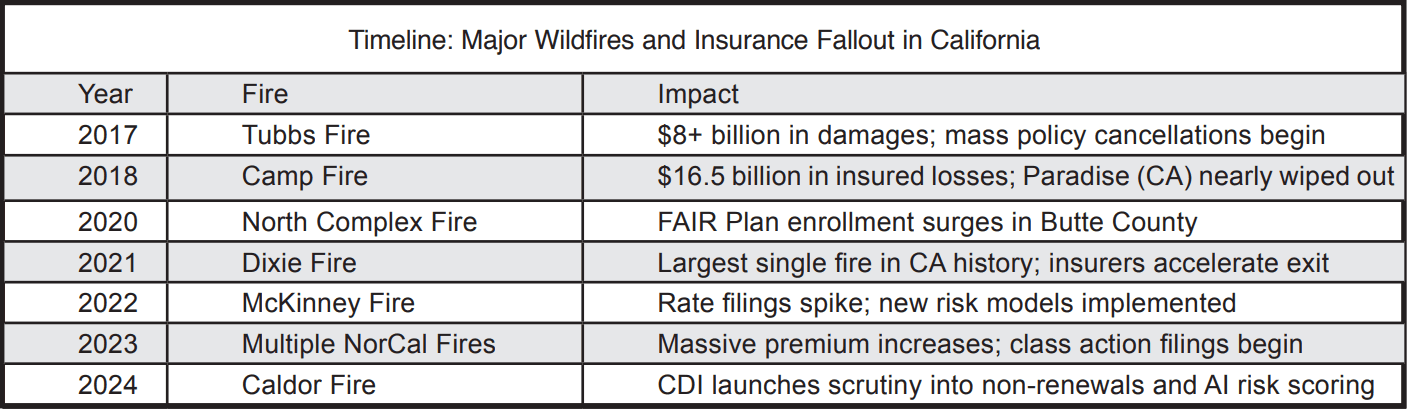

Financial Risk

California’s wildfire frequency and intensity have dramatically increased over the past decade. Climate change has made the environment more combustible, while electrical utility mismanagement has exacerbated ignition risks. It has grown longer, hotter, and more destructive every year. In 2023 alone, wildfires consumed over a million acres, displacing thousands and causing billions in damage. The result has been not only an unprecedented scale of destruction but also a corresponding financial crisis in the insurance sector.

As losses have mounted, insurance companies have reacted. Some have withdrawn from the California market entirely. Others have sharply raised premiums or stopped renewing policies in high-risk areas. This has placed immense pressure on homeowners who, after surviving a wildfire, face a secondary blow when their coverage is denied or withdrawn.

In theory, California’s FAIR Plan exists as a safety net for such situations. It is a state-mandated insurance pool that provides basic fire coverage when no standard carrier will underwrite a policy. However, the FAIR Plan is not a true replacement for comprehensive insurance. It covers fire but lacks coverage for liability, theft, and other common risks. It also comes with higher premiums and fewer benefits, making it an unattractive but sometimes unavoidable fallback.

A lesser-known legal twist further complicates the situation. Admitted carriers in California are statutorily tied to the FAIR Plan through indemnity obligations. If the FAIR Plan faces large losses, participating carriers share responsibility for covering those costs. This creates a financial incentive for admitted insurers to reduce their own exposure in fire zones — not only to limit direct losses but also to avoid secondary liability through FAIR Plan assessments. Consequently, these carriers are reducing policy issuance in fireprone regions, forcing more consumers onto the FAIR Plan and creating a feedback loop of declining private coverage and rising public burden.

The Insurer of Last Resort — and Why Admitted Carriers Are Reassessing Their Footprint

The California FAIR Plan is a state-mandated insurance pool designed to provide basic property coverage for homeowners and businesses who cannot obtain insurance through the voluntary market. FAIR Plain is designed to quite literally be the insurer of last resort. The FAIR Plan was established in 1968 following the riots and brush fires of the 1960s. The FAIR Plan became the state’s insurer of last resort, providing access to fire coverage for California homeowners unable to obtain it from a traditional insurance carrier. Californians cannot apply directly for coverage as they may with an admitted carrier. Rather, applicants must apply through a broker who can attest that they were unable to place coverage with an admitted carrier. This additional step provides that the FAIR Plan is the “last resort” policy for high-risk properties. Despite the fact that the admitted carriers must decline to cover the property, the way FAIR plan is funded has far-reaching implications for every admitted insurance carrier operating in the state.

How Indemnity Payments Are Shared Among Admitted Carriers

When the FAIR Plan pays out a claim, the money does not come from a single insurer. Instead, all admitted carriers in California are required to reimburse the FAIR Plan for their proportionate share of those indemnity payments. The formula is based on each carrier’s market share of written premiums in the state and the carriers cannot just pass those reimbursements through directly to the insured.

For example, if an admitted insurer writes 10% of the total property insurance premiums in California, it is responsible for 10% of the FAIR Plan’s losses, regardless of whether any of its own policyholders were involved. This applies not only to the initial claim payment but also to excess indemnity exposure — situations where catastrophic losses exceed the FAIR Plan’s reserves.

Why Carriers Are Pulling Out of Low-Risk Areas

Because FAIR Plan reimbursement obligations are tied to overall market share, carriers with large policy portfolios in California — no matter where those properties are located — face higher proportional liability for FAIR Plan losses. This has created a counterintuitive incentive:

Some insurers are withdrawing from relatively low-risk areas or non-catastrophe-prone markets to reduce their overall insured footprint in California. By writing fewer policies statewide, they shrink their share of the FAIR Plan’s exposure.

Although the California FAIR Plan’s indemnity reimbursement structure directly impacts admitted carriers, those costs do not remain solely on the insurers’ books. California law allows admitted carriers to factor FAIR Plan loss assessments into their rate filings with the Department of Insurance (CDI), but they cannot automatically pass through the entire cost dollar-for-dollar.

California has one of the most restrictive rate-regulation systems in the country under Proposition 103. Any carrier wishing to raise rates must submit an actuarial filing to the CDI demonstrating that the proposed increase is justified based on loss experience, expenses, and a reasonable profit margin.

When it comes to FAIR Plan reimbursements, regulators scrutinize:

- Actual, not projected, costs — Carriers must show historical FAIR Plan charges, not speculative future liabilities.

- Proportional impact — Only the portion of FAIR Plan expenses directly tied to insurable risk and actuarial necessity can be included.

- Public interest — The CDI can reject or scale back proposed increases if deemed excessive, even if the carrier’s FAIR Plan costs are higher

As a result, while some FAIR Plan costs can be factored into rates, regulatory oversight prevents carriers from fully shifting the financial burden to policyholders.

While FAIR Plan funding is designed to spread the cost of insuring high-risk properties across all admitted carriers, the regulatory limits on cost recovery mean that some of those expenses stay with the insurers.

The result is a market where availability and affordability are declining not just in wildfire zones, but also in communities far from high-risk areas.

Why This Only Impacts Admitted Carriers

Importantly, this funding structure only applies to admitted carriers — those licensed and regulated by the CDI. Non-admitted insurers (surplus line or special unique insurance not usually covered by other insurers due to risk) are not part of the FAIR Plan pool and therefore bear no responsibility for reimbursing FAIR Plan losses. Non-admitted insurance carriers are regulated in their domiciliary jurisdiction and must be eligible under federal and California law before business in California can be placed with them. Before a risk is placed in the surplus line market, the surplus line broker must ensure that insurance is not generally available from admitted insurers qualified to write that type of insurance.

This difference is fueling a noticeable market shift: as admitted carriers retreat, surplus lines carriers are expanding their presence, often at higher premium rates and with less regulatory oversight.

The California FAIR Plan vs. Traditional Policies — How They Work Together and the Broker’s Role

While the FAIR Plan serves as a safety net, it is not a comprehensive insurance policy. FAIR Plan coverage is generally named-peril and bare-bones, protecting against specific risks such as fire, lightning, and smoke damage. It does not automatically cover theft, water damage, liability, or other common homeowner risks.

How FAIR Plan and Companion Policies Work Together

To fill these gaps, most homeowners pair a FAIR Plan policy with a “difference in conditions” (DIC) or wraparound policy issued by a private admitted or non-admitted insurer. This secondary policy covers the perils the FAIR Plan does not, creating something closer to a standard homeowner’s package when combined.

In practice:

- FAIR Plan = Core fire and limited peril coverage (can include wind)

- DIC/Companion Policy = Theft, liability, water damage, and other missing coverages (can include wind)

The two policies operate side-by-side, and claims are directed to the appropriate carrier depending on the peril that caused the loss.

Why Brokers Are Incentivized to Sell FAIR Plan Packages

Brokers often recommend the FAIR Plan + DIC combination when standard carriers decline coverage, especially for homes in wildfire-prone areas. However, commission structures are very different for FAIR Plan policies compared to standard policies:

- FAIR Plan commission: Historically low — often around 5% or less, and in some cases as low as a flat fee.

- DIC/Companion policy commission: Typically standard market rates (e.g., 10–15%), which can be more financially worthwhile for brokers.

Because of the low margins on FAIR Plan policies, brokers are incentivized to package them with higher-commission DIC policies, ensuring the homeowner gets comprehensive coverage while the broker can sustain a viable business model.

III. Allegations of Collusion: What’s Being Reported

Reports from attorneys, consumer rights organizations, and policyholders indicate that this strategic retreat from the California market may not be isolated conduct. Allegations are growing that major insurers are engaging in de facto or even de jure collusion.

One major concern is the synchronized nature of policy cancellations in specific high-risk regions. Rather than a patchwork of decisions based on each company’s proprietary risk assessment, the pattern suggests a coordinated response. Communities are suddenly finding themselves collectively uninsurable, raising the question of whether insurers are acting in concert to avoid servicing fire zones altogether.

Further scrutiny is directed at the use of third-party wildfire risk models. Insurers increasingly rely on complex, opaque algorithms developed by external vendors to evaluate fire risk and set premiums or determine insurability. While such tools offer a veneer of objectivity, they can also facilitate uniformity in decision-making across companies — especially when multiple insurers use the same models or data sources. This creates the appearance of collusion, even in the absence of overt agreements.

Moreover, anecdotal and statistical patterns point toward market manipulation. Coordinated withdrawals or premium hikes in targeted regions produce a chilling effect, eliminating consumer choice and effectively redlining entire communities. Whether through direct communication, shared risk analytics, or collective industry pressure, insurers appear to be orchestrating a withdrawal from wildfire-exposed regions in ways that limit competition and increase consumer harm.

IV. Legal Perspective: What Is Collusion in Insurance?

Under California and federal law, collusion among insurers — whether tacit or explicit — can constitute a serious violation. The legal framework governing such behavior spans several statutes and regulatory bodies, beginning with the fundamental definition of antitrust violations.

Collusion involves any agreement — formal or informal — between companies to restrain trade, fix prices, divide markets, or otherwise manipulate the competitive landscape. In insurance, this could include collective decisions to exit certain markets, uniformly raise rates, or deny coverage to specific categories of consumers.

California’s Insurance Code prohibits unfair and deceptive practices by insurers, and the CDI is charged with investigating and enforcing these rules. Additionally, the state’s Unfair Competition Law (UCL) broadly prohibits any unlawful, unfair, or fraudulent business practice. Conduct that violates the Insurance Code — or federal antitrust laws — can trigger UCL liability, allowing injured parties to seek injunctions, restitution, and potentially classwide remedies.

The Sherman Antitrust Act (federal) and the Cartwright Act (California’s state equivalent) both prohibit anti-competitive behavior. However, proving a collusion claim is notoriously difficult. Courts require more than just parallel conduct; there must be evidence of a conscious agreement. In industries like insurance, where risk models and regulatory frameworks can produce similar outcomes among competitors, distinguishing independent action from coordinated behavior becomes challenging.

Nonetheless, if insurers are using shared data sources, engaging in informal communication, or relying on common third-party vendors in a way that aligns their conduct, they may face exposure under antitrust laws. Evidence of industry meetings, email exchanges, or common contractual arrangements could serve as a basis for collusion claims.

V. Real-World Impacts: Voices from the Fire Zone

Although legal analysis can sometimes seem abstract, the stakes of insurance collusion are profoundly human. In fire-ravaged communities across California, homeowners have found themselves uninsured or underinsured — sometimes immediately after a fire, other times preemptively, based on risk models or zip code-based policies.

For many, the cancellation or non-renewal of their policies has made rebuilding impossible. Without coverage, they cannot secure construction loans, refinance mortgages, or meet the requirements of local building ordinances. Forced to rely on the FAIR Plan or go entirely uninsured, they are left vulnerable not only to financial ruin but also to further displacement.

From a legal standpoint, these consequences raise questions of consumer protection, access to housing, and equitable treatment. Denying insurance based on community-wide risk assessments — especially when driven by opaque or shared industry tools — can perpetuate inequality and environmental injustice. If such practices are found to be coordinated rather than independently derived, insurers could face liability for both individual and systemic harms.

VI. The Role of Reinsurers and Market Pressures

No examination of wildfire insurance in California would be complete without addressing the role of reinsurers. These entities, which provide insurance to insurers, exert significant influence on underwriting practices and pricing. As climate risks have grown, reinsurers have increased premiums or withdrawn support for certain markets, including wildfire-prone areas in California.

Some argue that primary insurers are merely reacting to these pressures. Without affordable reinsurance, they cannot feasibly offer coverage in high-risk zones. This raises the question: if insurers are reacting to external market signals, does that shield them from legal liability?

The answer is nuanced. While economic justification may explain certain behaviors, it does not automatically absolve companies of liability under antitrust or consumer protection laws. If insurers respond to market pressures by independently adjusting their business practices, that is permissible. But if they coordinate their responses — formally or informally — that coordination could cross legal lines. Moreover, using reinsurer withdrawal as a pretext to jointly exit or redline markets still implicates questions of fairness and legality

Legal scrutiny may also extend to the reinsurance industry itself. If reinsurers are applying coordinated pressure or creating bottlenecks that restrict consumer access to insurance, they too could face regulatory or antitrust exposure.

VII. State Response and Legal Remedies

In response to growing concerns, the CDI has begun examining insurer behavior in fire-prone regions. Investigations, policy hearings, and public statements suggest increased scrutiny, but enforcement action remains limited. The CDI’s challenge lies in proving coordination, especially when conduct appears algorithmically driven or economically justified.

Nevertheless, several legal remedies are available to affected consumers. One is the “bad faith” claim, which allows policyholders to sue insurers who fail to act fairly or in good faith when processing claims or renewing policies. Although bad faith typically arises from claim denials, it could extend to wrongful cancellations or manipulative underwriting if insurers are found to be circumventing legal obligations.

Additionally, civil actions under the UCL or Cartwright Act may be viable, particularly if consumer advocates or legal nonprofits initiate class actions. Such suits could seek injunctive relief, compel transparency, or secure damages for affected policyholders. Legislative proposals are also underway, aimed at mandating clearer underwriting standards, limiting arbitrary non-renewals, and ensuring that high-risk communities are not categorically denied insurance.

Finally, there are calls for greater oversight of thirdparty risk models and reinsurer influence. Regulators may soon require insurers to disclose how risk scores are calculated and what data is shared across firms, potentially curbing the shadow coordination facilitated by shared technologies.

VIII. The Bigger Picture: Insurance, Justice and Climate Resilience

At its core, the California insurance crisis is not just about business decisions — it is about justice, equity, and climate adaptation. As climate risks intensify, the existing insurance model may no longer be sustainable. Yet the solution cannot be mass abandonment of vulnerable communities by the insurance industry.

Some legal scholars have proposed treating insurance more like a public utility, especially in disaster-prone areas. If private markets fail to provide essential services equitably, state intervention may become necessary. This could take the form of public insurance programs, mandatory coverage obligations, or new regulatory regimes.

Ultimately, legal reform must be part of a broader societal reckoning. In a climate-constrained world, wildfires will continue to devastate communities. Ensuring that survivors can rebuild — both physically and financially — requires more than sympathy; it demands structural protections. Insurance must be part of the resilience strategy, not an added source of trauma.

The path forward involves rethinking how we regulate, deliver, and monitor insurance services in California. Without meaningful reform, wildfire victims will continue to be burned twice: once by nature, and again by a system designed to protect them.

you might also like

Burned Twice: Insurance Collusion Is Compounding the Wildfire Crisis

After the January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires, survivors faced a second crisis: canceled policies, rising premiums, and rebuilding obstacles. This article explores whether insurers’ synchronized pullbacks and shared risk tools could amount to unlawful collusion under California and federal law.

Slip and Fall Injuries in Los Angeles: How Negligence Is Proven in Premises Liability Cases

Slip and fall injuries are often treated like minor accidents, but many are caused by preventable hazards. Understanding how California premises liability law works—and what it takes to prove negligence—can help injured victims protect their health, finances, and legal rights.

Concussion Symptoms After an Accident: Why Head Injuries Should Never Be Ignored

Concussions are often misunderstood as minor injuries, but the truth is that symptoms can appear gradually and worsen over time. Understanding how concussion injuries work, why documentation matters, and how California personal injury claims address head trauma can help victims protect their health and their rights.

The Woolsey Fire: Understanding Legal Accountability After a Devastating Wildfire

The Woolsey Fire left a lasting mark on Southern California, destroying homes, displacing families, and reshaping conversations around wildfire responsibility. For victims, understanding legal accountability became a critical part of recovery.

The Thomas Fire: Legal Accountability After a Historic California Wildfire

The Thomas Fire was one of the largest and most destructive wildfires in California history. Beyond the physical devastation, it became a turning point in how wildfire responsibility, liability, and large-scale disaster litigation are addressed.

San Diego Floods (2024): When Infrastructure Failure Turns Into a Legal Crisis

The 2024 San Diego floods exposed serious infrastructure failures that left homes and businesses underwater. As recovery began, questions of responsibility and accountability became central for affected communities.